Good day to you all

This is Sergeant James Mendick back again, reporting on crimes old and new. Today I am going to talk about one aspect of criminal Aberdeen. Now you all know that today we have a dedicated, skilled and professional body of policemen, like myself, dedicated to keeping Good Queen Victoria’s towns and cities free of crime and criminals so that the respectable people such as yourselves can walk in safety.

It was not always so. Once there were only a very few overworked individuals to guard the populace from the hordes of the wicked. In Aberdeen up in the north east of Scotland there were the Town Sergeants.

Of all the Town Sergeants, Charles Dawson was perhaps the best remembered. He lived at Well Court in Broad Street and became legendary for his knowledge of all the local bad men. Dawson was a busy man as he kept his stern eye on the bad characters of the town. One family that stirred his interest were the Pirie brothers: John, Peter and Thomas Pirie, who were known thieves and housebreakers. If the criminologists’ theory of a criminal class was ever true, the Piries were role models. When there were a number of burglaries in the winter of 1829, Dawson looked at the modus operandi, checked the whereabouts of the Pirie clan and put his detective skills to work.

The first break-in that Dawson could connect with the Piries occurred on the night of 14 November 1829. Burglars had hit the firm of William Mackinnon and Company, Iron and Brass founders of Windy-Wynd. This was a lane that ran between Spring Gardens and Gallowgate, where the north bank of Loch of Aberdeen had been. The burglars were not subtle. They forced open an iron front door to enter a short corridor that led into the premises. There was a second, wooden door with a lock that was nailed in place. The burglars forced this lock as well. That door led into a space from which doors opened onto a tin workshop and a copper workshop. The door to the tin shop was open and the iron shutters to the copper workshop had been thrust back; there had been a fair amount of strength needed to break in.

The burglars stole a variety of objects that could be kept, pawned or sold: a number of tin dishes, a zinc-brass cover, two brass pump valves, files, brass fire irons, an oil flask, a bow saw and other objects. Dawson notified the pawn shops about everything that had been stolen.

The second break-in that Dawson linked to the Piries was on 12 December 1829 when the home of Harry Grassie was burgled. Grassie lived at Holburn on the road from Union Grove to the Deeside turnpike. Once inside, the burglars had emptied a desk of promissory notes and bills, an insurance policy, £9 in bank notes [more than a junior domestic servant earned in a year], pocket books and various personal and business papers.

Dawson and the police asked for more details of the Holburn break in. Harry Grassie was an elderly man with money, but in a move that was not uncommon at the time, he had married a young and attractive wife. His wife had fallen foul of the excise and had been fined, but Grassie had refused to pay the fine so she was jailed instead. Despite his apparent callousness, Grassie visited his wife in the jail every night between six and seven. Ironically, or perhaps with poetic justice, it was when Grassie was visiting the jail that the burglars struck, removing a pane of glass from the bedroom window to get in.

Dawson investigated the break in with a careful eye that would have found favour with Sherlock Holmes. He found three sets of footprints on the earth underneath the bedroom window. He measured the prints; one was quite distinct as if the heel had been lost from the boot, so that could have been a valuable clue: now all Dawson had to do was search all of Aberdeen for a man with no heel on one of his boots.

Although Dawson suspected that the Piries may have been involved in the factory robbery, he had no evidence against them. However when he examined Pirie’s house in Ann Street, he took Grassie in case there was any of his property to identify. He also brought and two other men in case of trouble. After Dawson banged on the door for a good fifteen minutes, the Piries allowed him in. Dawson asked to see all the boots in the house. There were three pairs; all dirty but that was not unusual at a time when paved streets were not universal. The boots were an exact match in size for the footprints on the earth, and one was lacking half its heel. Dawson guessed that he had found his burglars and immediately arrested them.

He searched the house and found two chisels, one of which had a piece of putty on the blade, which suggested it had been used to remove a pane of glass from a window. The colour of the putty on the blade matched that around the glass on Grassie’s window. Dawson searched further; he lifted the hearthstone and found a snuff box with Grassie’s bills inside. There seemed no doubt that the Pirie’s had burgled Grassie’s house.

However there remained the Mackinnon burglary. Although Dawson had no evidence, he strongly suspected that the Piries were involved there as well. He remained alert and asked his informants to keep their ears open for any information. The Piries lived right next door to Mackinnon’s foundry and worked in a factory in nearby Wapping Street. As the weeks passed they must have thought they had escaped, but when Charles Dawson arrested them for the break in at Grassie’s, one of their work mates, William Ross remembered one of the Piries using a bow saw. Ross recollected that such an item had been stolen from Mackinnon and searched the factory further. In a hidden corner of the factory he found three bags of material that had been stolen from Mackinnon. Ross took the bags to the Police Office.

Working closely with the police, Dawson questioned Pirie’s neighbours and their servant, a woman named Moir. She lived in the flat immediately below Grassie and knew his house well. She told Dawson that John Pirie had asked her to sell a set of brass fire irons for her. When Dawson asked, she handed him the irons, which were the set that had been stolen from Mackinnon. There was more than enough evidence to charge John Pirie with the Mackinnon break in.

The case came to trial in the April Circuit Court. The Piries pleaded not guilty and put up a spirited, if strange defence of alibi. Although there had been a number of people who were definite that they had seen the Piries leave their work early on the Saturday afternoon, the Piries found counter witnesses who had apparently seen them hard at work. One woman, Agnes Faulkner, swore blind that she left the work with John Pirie at quarter past six, and that she accompanied him to the Ann Street house, where she remained until quarter past eight. Even stranger, the Piries had a sister who put herself square in the firing line when she claimed that her husband had brought home the box full of Grassie’s bills, and told her to hide them. She claimed that she had not known they were stolen, but she had placed them under the hearthstone, without her brother’s knowledge. When the Advocate General heard that this woman was estranged from her husband, he prevented her from continuing, as she might incriminate him.

After hearing from four Glasgow criminal officers that John Pirie was a well known thief, the jury found him guilty of the Mackinnon burglary, but the case against his brothers was not proven. All three were found guilty of the Grassie burglary. John Pirie, the eldest brother, was transported for life and his two brothers for seven years. The Pirie brothers sailed on Burrell on 22 July 1830 along with another 189 convicts. The Pirie sister was not charged with perjury; although it seemed obvious she was more concerned with getting her husband in trouble than ensuing that justice was done.

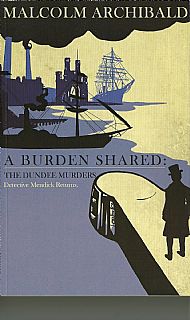

If I say so myself, that was not a bad result for a man who worked without training. Of course if you want to read about a real criminal officer in action, two of my own stories, Darkest Walk and A Burden Shared are in print. . .

http://www.malcolmarchibald.com